As some of you may know matrix multiplication is associative (a.k.a. all the parenthizations give the same result). But when you carry out the computation you have to choose some order. But associativity makes this irrelevant, right?

Consider:

Matrix = np.ndarray

@dataclass

class Parenthization:

left: Parenthization | Matrix

right: Parenthization | Matrix

def random_matrices(n: int) -> list[Matrix]:

dims = [random.choice((1, 100)) for _ in range(n + 1)]

return [np.random.randn(dims[i], dims[i + 1]) for i in range(n)]

def random_parenthization(matrices: list[Matrix]) -> Parenthization | Matrix:

if len(matrices) == 1:

return matrices[0]

k = random.randint(1, len(matrices) - 1)

left = random_parenthization(matrices[:k])

right = random_parenthization(matrices[k:])

return Parenthization(left, right)

def get_product(node: Parenthization | Matrix) -> Matrix:

if isinstance(node, Matrix):

return node

return get_product(node.left) @ get_product(node.right)

if __name__ == '__main__':

matrices = random_matrices(100)

parenthizations = [random_parenthization(matrices) for _ in range(1_000)]

performance_barplot(parenthizations, get_product)

TLDR: For a given product of matrices, generate a bunch of random parenthizations and see how long they take to compute.

Which gives us:

420- 600 ms │ ████

600- 780 ms │ ██████████████████

780- 960 ms │ ████████████████████████████

960- 1130 ms │ ████████████████████████████████████████

1130- 1310 ms │ █████████████████████████████

1310- 1490 ms │ ██████████████████████████

1490- 1670 ms │ ███████████████████

1670- 1840 ms │ ████████████

1840- 2020 ms │ ████████████

2020- 2200 ms │ ██████

2200- 2380 ms │ ███

2380- 2550 ms │ ███

2550- 2730 ms │ ██

2730- 2910 ms │ █

2910- 3090 ms │

3090- 3260 ms │ █Holy mother of performance-variance-for-semantically-equivalent-expressions!

But why does this happen??

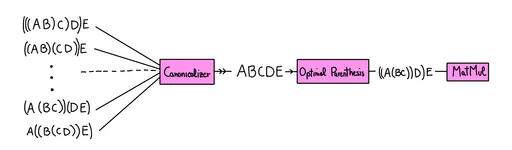

Different Parenthization => Different Dimensions! Multiplying an

XbyYmatrix with aYbyZmatrix takes aboutO(XYZ)scalar ops (XYZ multiplications, X(Y-1)Z additions). So on the LHS each pairwise product takes 1 op, in the RHS about 2 million!

Oh yeah that makes sense! But how do we fix it? Boringly, with some DP:

def optimal_parenthization(matrices: list[Matrix]) -> tuple[int, Parenthization | Matrix]:

n = len(matrices)

if n == 1:

return 0, matrices[0]

dims = [matrices[0].shape[0]] + [m.shape[1] for m in matrices]

mult_cost = lambda i, k, j : dims[i] * dims[k + 1] * dims[j + 1]

@cache

def solve(i: int, j: int) -> tuple[int, Parenthization | Matrix]:

if i == j:

return 0, matrices[i]

best_cost, best_tree = float("inf"), None

for k in range(i, j):

left_cost, left_tree = solve(i, k)

right_cost, right_tree = solve(k + 1, j)

cost = mult_cost(i, k, j)

total_cost = left_cost + right_cost + cost

if total_cost < best_cost:

best_cost = total_cost

best_tree = Parenthization(left_tree, right_tree)

return best_cost, best_tree

return solve(0, n - 1)TLDR: To find optimal parenthization: for all the ways to split the list into 2 contiguous chunks, recursively find the cost of the 2 sub-chunks, and add sum them to the cost of doing the top-level multiplication. Then find the minimum value: that is the optimal parenthization!

But, ew. Now our code logic is tangled up with implementations details concerning runtimes. How do we address this?

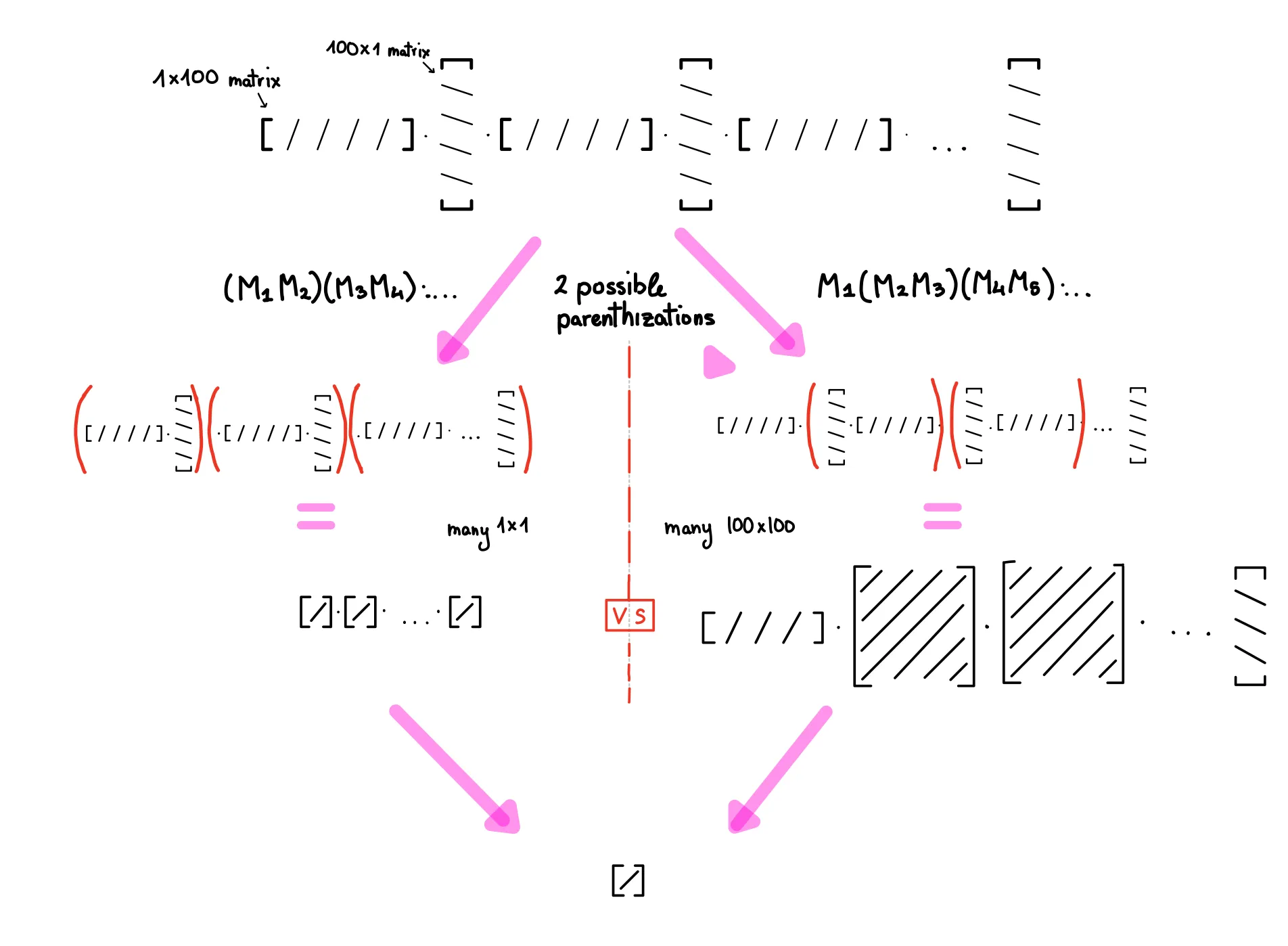

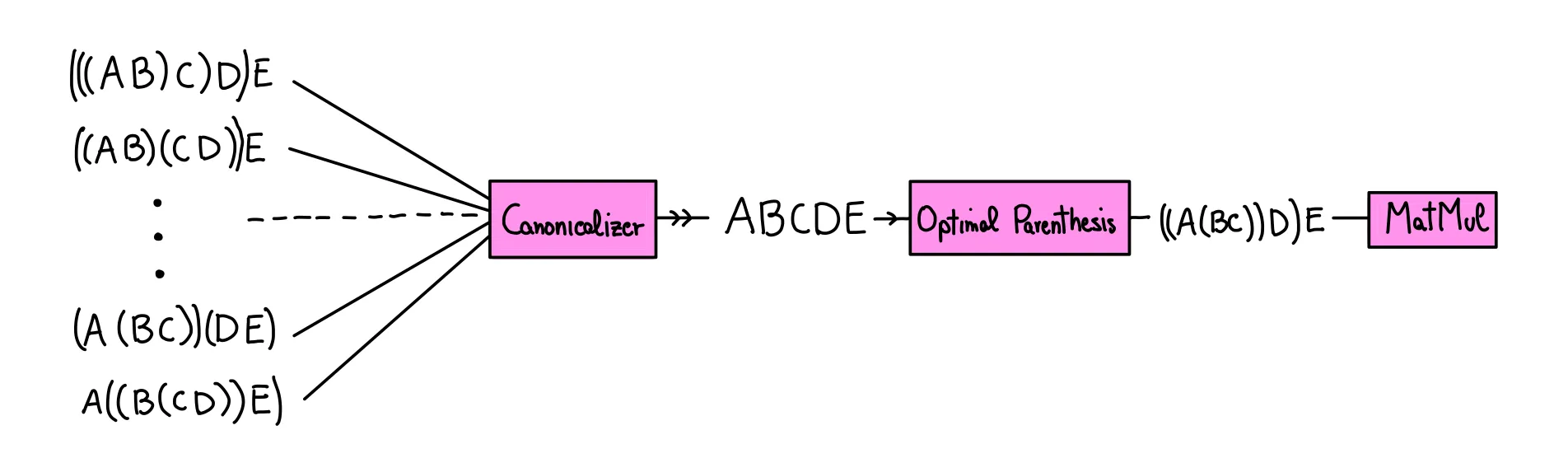

Ideally something like this:

But here’s the problem: the matmul is supposed to always be a single matrix (the product of all the matrices up to that point). But now you are representing it as a tree (of parenthesis)! Solution: just collapse it down to a single matrix when the user “looks” at it! (a.k.a. when the explicit value of the matrix is needed: as long as we keep multiplying, we can just keep building up the list). So we can do something like this!

@dataclass

class LazyMat:

matrices: list[Matrix] = field(default_factory=list)

def __matmul__(self, other: Matrix | LazyMat) -> LazyMat:

if isinstance(other, Matrix):

return LazyMat(self.matrices + [other])

if isinstance(other, LazyMat):

return LazyMat(self.matrices + other.matrices)

raise NotImplementedError

def __rmatmul__(self, other: Matrix | LazyMat) -> LazyMat:

if isinstance(other, Matrix):

return LazyMat([other] + self.matrices)

if isinstance(other, LazyMat):

return LazyMat(other.matrices + self.matrices)

raise NotImplementedError

def value(self) -> Matrix:

_, tree = optimal_parenthization(self.matrices)

prod = get_product(tree)

self.matrices = [prod]

return prod

def __array__(self, dtype=None):

out = self.value()

return np.asarray(out, dtype=dtype) if dtype is not None else outSo now we passively build up the tree each time we do a matmul, and use .value() when we need the matrix itself. Cool!

Now for the speedup over eager:

def random_matrices(n: int) -> list[Matrix]:

dims = [random.randint(10, 1000) for _ in range(n + 1)]

return [np.random.randn(dims[i], dims[i + 1]) for i in range(n)]

def naive_product(chain):

"""(((A @ B) @ C) @ …)."""

out = chain[0]

for m in chain[1:]:

out = out @ m

return out

def lazy_product(chain):

"""Wait to evaluate, then do the optimal parenthization"""

acc = LazyMat()

for m in chain:

acc = acc @ m

return acc.value()

def bench(fn, mats, runs=10):

t0 = time.perf_counter()

for _ in tqdm(range(runs)):

fn(mats)

return (time.perf_counter() - t0) / runs

if __name__ == "__main__":

random.seed(0); np.random.seed(0)

mats = random_matrices(100)

t_naive = bench(naive_product, mats)

t_lazy = bench(lazy_product, mats)

print(f"Naïve left‑to‑right : {t_naive*1e3:7.1f} ms")

print(f"Lazy optimal : {t_lazy*1e3:7.1f} ms")

print(f"Speed‑up : {t_naive/t_lazy:7.1f}×")Naïve left‑to‑right : 2298.8 ms

Lazy optimal : 227.0 ms

Speed‑up : 10.1×But it doesn’t have to end there! We can also act lazily with respect to a whole bunch of over operators. This allows us to do 2 things:

- Right now, each non-matmul operation forces us to compute the entire tree: the more operators we support, the more we can keep the lazy representation!

- More operators => more opportunities for optimizations. E.g. if matrix addition is supported, we can do this:

AB+AC->A(B+C)!

Stay tuned for part 2…

Takeaways

- Canonicalization and structured representations are pretty cool I guess?

- With good “compilers” and lazy evaluation, you can separate logic from performance details.