Summary Main Points See also Gödel’s Proof

How the self emerges from the aggregation of the selfless

Introspection is Possible, Transcendence is notNumber theory can talk about itself, but it can never escape the rules that define it (we can at most escape to a more general system, which is still bound by the same rules). This why the Godel trick works. The same is true for brains.

Every aspect of thinking can be viewed as a high level description of a system which on a low level is governed by simple/formal rules. Emergent Behavior is incredibly powerful: from a small set of simple rules emerges an ocean of complexity.

Strange Loops and Tangled Hierarchies

Consciousness:, when, due to self-reference, meaning emerges from a meaning-free universe. The self emerges from self-referencing. The concept of Self is stored throughout the brain. Gödel’s sentence G gives meaning to itself, by virtue of existing.

Tangled Hierarchy: one where the rules, the meta-rules, the meta-meta-rules, … are hard/impossible to distinguish, and can freely influence each other. Consciousness is an emergent behavior that arises from tangled hierarchies!! There is always a point where we reach an un-mutable substrate of rules (e.g. the fact that neurons obey the laws of physics) but they are inaccessible to us and so removed from the tangled hierarchy of mental symbols that it doesn’t matter as much.

Strange Loops: emerge when we have Tangled Hierarchies. Intelligence works by having many levels of rules, which are able to change and rearrange each other.

Free Will: emerges from the balance between introspection (being generally aware of why we make choices, and being able to work on different levels of description) and ignorance of our inner workings (e.g. we don’t know which neurons are triggered exactly etc…). So free-will is an emergent behavior!

The soul can emerge from purely mechanical parts, since we can have meaning emerge from meaning-less components.

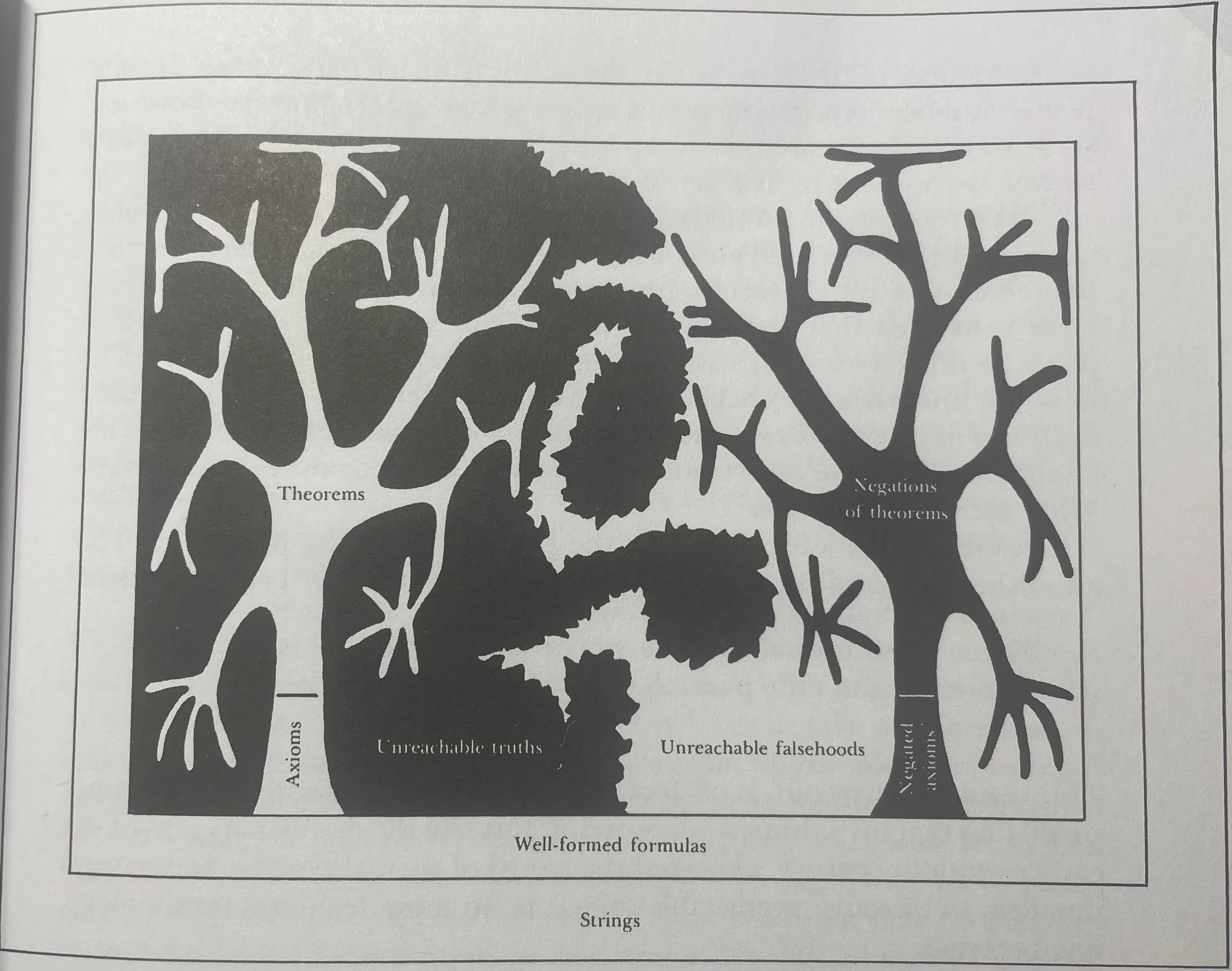

Completeness and Consistency

Gödel’s insight: statements of number theory are about numbers, not statements themselves. BUT, if you can encode statements as numbers, then a statement can be about numbers as well as statements (possibly even itself!).

If the system could prove the Gödel sentence to be true, it would contradict its consistency, and if it could prove the sentence false, it would lead to a logical contradiction. Therefore, the statement is true but unprovable within the system.

We would like to show that the set of all false statements of number theory can be characterized as both:

- The negative space to the set of all theorems

- The negation of all true theorems BUT, this can’t happen, since:

- There are some “unreachable” truths (statements which are true but are not theorems)

- There are some unreachable “falsehoods”, (statements which are false but are not theorems)

Consistency and CompletenessConsistency

- Internal: the theorems within the system don’t contradict each other

- External: the theorems true within the system correspond to a truth in the real world (e.g. 2+2=4 and 2 apples + 2 apples is 4 apples)

Completeness All true statements can be proved (a.k.a. are theorems)

Consistency: everything produced by the system is true Completeness: everything true is produced by the system

Formal Systems

For well-formedness of a given string (according to a certain formal system), we can device predictably terminating tests. For theoremhood, correctness, by the Church-Turing theorem, we can’t!

The same is true for human experiences:

- Some qualities are syntactic, and “easy to prove”

- Some qualities are semantic, and can be tested with a simple decision procedure. Also they depend partially on the interpreter (ie the person experiencing it) Beauty is a type of semantic quality!

Principia Mathematica (PM)

Is born to banish “strange loops” (such as the one originated from Russell’s paradox) from formal mathematics, by defining a strict hierarchy among sets, which makes self-reference impossible. Gödel demolishes is, proving that any axiomatic system (such as PM) is either incomplete or inconsistent.

MU and pq

Example of formal system. By applying the formal rules, and starting from an axiom, we produce new strings / theorems. Humans are great in and out of systems:

- Within the system: using the rules to construct strings.

- Outside the system: making observation about the system itself. A system is characterized by:

- A set of axioms

- A decision procedure, a.k.a. a test that determines in a finite amount of time whether a given theorem is true (or better, deducible). Having axioms only characterizes the system weakly!!

To show that a property is common to all theorems, you can show (essentially doing induction) that the axioms have that property and that that property is inherited.

To prove a theorem in pq (where the theorem/string only becomes longer):

- Bottom Up: start from axioms, generate all theorems until we find the one we’re looking for (or we start generating strings longer than the one we’re looking for).

- Top Down: start from the theorem, work out way back (generating strings that are shorter and shorter) until we either find an axiom or we reach a dead end. This only works because the strings become longer and longer.

pq is a complete system, because it’s too weak of a system to run into Gödel’s Incompleteness theorem.

Formal systems may start meaningless but, by isomorphism with some aspect of reality, take on meaning of their own!

Surprisingly, the set of non-theorems of a certain system cannot always be expressed as the set of theorems of another system: There are systems for which their negation (set of nontheorems) is NOT the positive space of some formal system. Thus: There are systems for which there is no decision procedure!!

MU Puzzle

Is MU a theorem? No, just use as an invariant the number of ‘s mod 3 and see that it’s never equal to 0. We solve the MU-Puzzle by embedding the MU-System within number theory.

Propositional Calculus

There are no axioms, only rules, so the theorems will always be implications (if P -> Q). At a certain point, you must blindly trust the patterns of reasoning: you can prove them, but then you would have to also prove the proof itself is valid, etc…

Typographical Number Theory (TNT)

We’re trying to construct a way to characterize all true statements typographically. Systems like TNT serve as the basis, as they are then embedded into wider, more relaxed contexts where we can derive new rules of inference: the systems isn’t more powerful, it’s simply more usable.

Variables can be:

- Free (string expresses a property, like )

- Quantified (string expresses a boolean, like s.t. )

Systems can be -incomplete, if we can prove a certain that all theorems are true individually, but we can’t prove (i.e. the string is not a theorem) that

A statement is undecidable if it cannot be proven true (or false).

To prove TNT’s consistency, we must use a weaker system of reasoning (e.g. propositional logic + a few extra rules): if we use something as strong as TNT itself, we run into circular logic. The idea is that we don’t need all the properties TNT has in order to prove that TNT is consistent. BUT Gödel showed that any system that can prove TNT’s consistency is at least as strong as TNT itself, meaning circularity is inevitable!!

Order and Chaos

Nature (and number theory) present us with a host of phenomena which appear mostly as chaotic randomness until we select some significant events, and abstract them from their particular, irrelevant circumstances so that they become idealized.

Chaos is (sometimes) just unseen order!

No decision procedure for truth

Church Turing Theorem: there is no decision procedure for telling true from false statements in number theory. (bc Godel’s formula G is either a theorem (true and provable), but we know, by definition of G, that it’s not a theorem, or it’s not a theorem, meaning that “G is not a theorem” is a theorem, but this formula is G).

We cannot embed theoremhood about number theory within number theory itself. We’re not able to completely model truth!

At a high-enough level, the computations done by a machine and those done by a human are isomorphic (e.g. while there isn’t a low level mapping, say between transistors and neurons, there is between the high-level steps being done by the two are the same).

But brains are a very complex formal system, since there is no “real world” interpretation of the events that happen at a neural level (vs a computer, where the single instructions being executed to have meaning).

Computers can be irrationals, even if their atomic components act rationally (the same way in which the neuron’s act according to natural laws, but the brain can still act irrationally).

A Turing complete language is sufficient to simulate any sort of mental process. (Since we can describe / compute all that is computable with it)

Gödel’s Proof

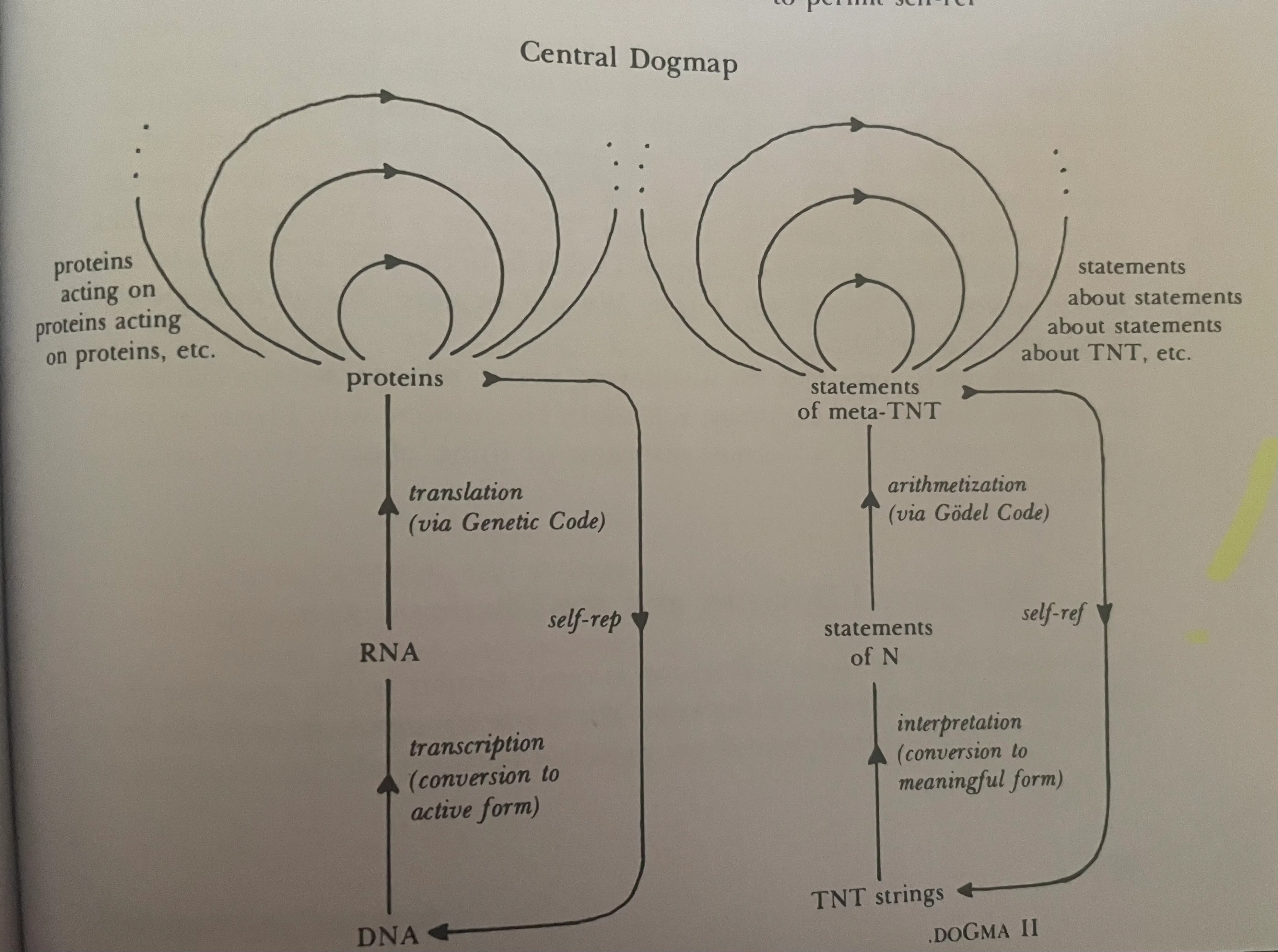

Gödel Numbering

A way to embed any formal system within number theory, allowing us to explore the formal system using the tools of number theory.

The idea is that any (e.g. typographical, like MU) rule present in formal system can be translated as an arithmetical rule, and the theorems into natural numbers.

This allows us to construct an isomorphism between numbers and theorems about number themselves!!

Every formalization of number theory has its meta language embedded within it.

Preferrable Systems

Mathematics only tells you answers to questions in the real world after you have taken the one vital step of choosing which kind of mathematics to apply.

There is no “real” number theory (or formal system in general), only systems which are more or less isomorphic to a given situation we want to describe.

Deciding which formal system fits best the given situation is an extra-mathematical judgment.

Halting Problem

Bounded Predicates(or primitive recursive): something that can be computed/verified in a predictably finite amount of time. (so essentially only finite loops) e.g. testing if a number can be written as the sum of 2 primes (we simply iterate over all finite pairs and check if there is a pair where both are primes) Gödel’s method is applicable to a given system when all primitive recursive predicates can be represented within it.

But for some functions / predicates one cannot give a bound to the number of calculations (e.g. we can find one using an argument similar to Cantor’s diagonalization argument, see page 420). Unbounded Predicates: Something that contains a (potentially) endless loop, meaning that it can potentially terminate, but we can’t determine when or if. e.g. testing if a number is the difference of 2 primes (since we need to check for infinitely many pairs, and we can terminate but maybe go on forever).

Can we determine if a unbounded program always terminates? No, by the halting problem. if we had it, it would be pretty incredible since, to test if a conjecture is true for all inputs (e.g. the difference of 2 primes conjecture), we just pass to the halting-detection machine a procedure that checks for it (e.g. tries all pairs, possibly infinitely many) and it would tell us if it terminates or not (and thus if the conjecture is true or not). So there are problems which are not solvable by computation.

The Proof

The proof relies on the fact that certain statements (and thus, by Godel numbering, a number) talk about themselves, meaning that number theory has an introspective power.

We can encode the statement ” is a TNT-theorem-number” in TNT itself. Our objective is to construct a Quine (so a statement about a given theorem/godel number which has as godel number itself.)

By doing double quinification, we can construct a statement G that states: “G is not a theorem within TNT”. This means that TNT is either:

- G is a theorem, in which case we have a contradiction

- G is not a theorem within TNT, which implies that G is true. But since it’s not a theorem, it can’t be proved. (n.b. theorem means true and provable)

Godel also proved that the statement “TNT is consistent” is only a theorem (i.e. true and provable within TNT) only if TNT is inconsistent!

So G forms a hole, since it’s an undecidable proposition! This means we can extend TNT, by postulating either G or ~G. Even postulating ~G creates a consistent system!

But this system doesn’t plug all holes! This new system is at least as expressive as TNT, and we can use the same technique to create a new godel sentence G’ which makes a new hole. We can’t even plug the hole by adding an axiom schema which sets as true G, G’, G”, etc…, since if we can describe them typographically, we can express them through a godel number, and so we can construct a godel sentence that defeats it.

Any system, no matter how tricky / complex, can Godel numbered, which makes it vulnerable to Godel’s trick

Counterargument

But what if there exists another system, alternative to TNT, which is not vulnerable to Godel? We have seen above that any system derived from TNT (so that it contains it) is vulnerable, but what if there was another system.

The possibility of constructing G depends on 3 factors:

- System is rich enough to express all statements about numbers

- You can model recursive relationships (so also stuff like induction)

- You can always differentiate between valid and invalid proofs.

But the system’s power is exactly what causes the hole! So it’s precisely the system being powerful enough (at least as powerful as TNT) that causes the hole.

Better than Machines? No

Does our ability to do Godelization make use better than machines (which can’t, since if we can describe it as a standard procedure, then we can apply the Godel trick again to this new system, which breaks it)? No, since we also have limits in our ability to apply the trick. Essentially, Godel’s trick makes it impossible to create a schema, since as soon as we create a schema, it also becomes vulnerable

The Myth of Self-TranscendenceWe can never truly jump out of ourselves, since while doing so we are still following the rules which define us

Self Reference / Recursion

Recursion is based on the “same” thing happening on several different levels at once. But the event on different levels aren’t exactly the same - rather, we find some invariant feature in them, despite many ways in which they differ. pg. 148

Intelligence is about a program that can recursively modify / observe itself.

Quines operate by constructing a self-reference by describing another entity which is isomorphic to the description itself.

The most exemplary cases of self-references are the ones where the heavy lifting is done by the sentence itself, not by the context (so they contain all the information to reproduce themselves (e.g. a piece of paper isn’t self-referential even though it can be copied, since the info to copy lays outside of the paper (e.g. in a printer))).

Copy: if it contains the same information as the original, and that information is stored in such a way that it can be mapped to the original way it was stored in a fairly trivial manner (e.g. a mirrored image is a copy of the original, even it’s stored slightly differently).

Biological Replication, DNA

Within biology, DNA strands are both the data being manipulated and the rules of inference themselves.

So each time we derive a new strand by manipulating existing ones, we also create a new rule to manipulate them! (Essentially, theorems and rules of inference are one and the same).

So strands translate into enzymes, which “execute” and create new strands, which in turn define new enzymes etc… (In genetics, the contribution that an amino acid does is not context free (ie depends also on the surrounding amino-acids, so it’s not like assembly where each instruction / amino-acid has a clearly defined role).

Enzymes can operate on anything: DNA, RNA, other proteins, ribosomes etc…, essentially anything that is made of aminoacids.

We can create a self-reproducing (~quining) DNA strand, which contains the information to copy itself and is executed on itself.

We can read DNA as different levels, from low (e.g. this is a sequence of bases) to medium (e.g. this is a sequence of proteins) to high (e.g. this sequence encodes a certain physical / psychological trait).

Viruses are in a sense the opposite version of a Godel sentence, since they contain, within themselves, the recipe for replicating. (so they are essentially the sentence “The following string … is a derivation of me”).

So within cells, the program, data, interpreter, processor and language are all interwoven, and all made up of DNA! (see page 547)

Location of Meaning

Message: the information-bearer (e.g. a string of text, a musical disk) Context: the information-receiver (e.g. the grammar rules, a jukebox)

How much of the meaning resides in the message vs the context? Depends on how important we consider the internal logical structure of the message: if it’s meaningless without the context to interpret it or if the logical structure is so strong that the context can be restored automatically by an intelligent enough species.

In an out-of-context message (e.g. a washed up bottle), information is divided in:

- Frame: physical aspect (a glass bottle with a scroll inside)

- Outer-message: symbols and patterns that have been decoded (the text inside the bottle)

- Inner-message: what the author wanted to communicate / elicit (e.g. a feeling of joy if it’s a song, etc…)

So to understand a message you need to understand its context. This is also a message, which means you have to understand its context, which in turn is also a message, etc… So how do we recognize messages? The brain, since it’s a physical object, can bridge the gap between physical and meaning.

Meaning is thus intrinsic to an object to the extent to which intelligence across the universe processes information uniformly (eg if all intelligences are able to recognize a list of prime numbers as such, then that list has intrinsic meaning)

There are no unencoded messages, only messages coded in a more or less familiar code of messages with a universal meaning

e.g. computers do not store numbers, that is just the a specific interpretation we give to the idea of storing one of 2 possible positions (bits) in sequence. Bongard Problems are a great example of messages with a universal meaning.

Zen

Enlightenment: transcending dualism, which is the conceptual and perceptual division of the world into categories. e.g. dualism words concepts, which is deceptive. Natural language is an incomplete and inaccurate system. Zen is holism to its logical extremes (everything is one).

Levels of Description

Intelligence can reason both within the confines of the problem and also about the confines themselves. We can jump between levels!The crux of intelligence is being able to smartly define a problem space and an associated metric that heuristically measures how close you’re getting to your objective.

We’re able to conciliate completely different level of descriptions associated to certain objects (e.g. we can simultaneously conceive ourselves both as a Self as well as an aggregate of molecules). We as humans can quickly switch between different levels of description! For example code, which can be understood both as machine code (so machine-dependent) and also as high level code (machine-independent).

Bootstrapping: using a smaller compiler to translate a bigger compiler into machine language.

Higher level languages don’t extend the capabilities of the computer, but rather abstract certain concepts, making it easier to explore certain regions of a specific “program-space”.

A program is (generally) not aware of the state of it’s operating system (e.g. humans and their immune system)

The higher the level of description of the system is, the most explanatory power it has, while also omitting to describe the fundamental building blocks (e.g. when explaining a book, we talk about the meaning of its words, not about the single letters).

When describing things, we can selectively exclude:

- Focusing: only consider certain entities

- Filtering: only consider certain attributes.

Holism: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts Reductionism: a whole can be understood as the sum of it parts Different levels of looking at a phenomenon imply different characteristics, which cannot be traced back to single components (e.g. ant colonies are smart, the individual ants are not).

Brain

State, Symbols, Signals and Units

4 levels to complex systems:

- Units: what makes up everything else

- Signal: is all structure and no content: when a signal goes through the brain, the information is carried, but the physical matter that makes up the signal changes continuously. Signals don’t have inherent meaning, but they make up symbols, which do have meaning.

- Symbols: are a unit of meaning (e.g. letters are signals, words are symbol). It activates other symbols when triggered (“spreading” the info). They are hardware realizations of concepts, mapping to something in the real world. Symbols can represent both classes and instances. Learning new information is about spawning a new instance symbol (which initially inherits heavily from its class symbols) which gradually becomes more and more independent the more we learn about it. (e.g. we learn about a new football player: initially the “football player” symbol fills in a lot of details, but the more we learn about him the more it becomes it’s own concept). Symbols are activated in a myriad of ways (various instance symbols together, a single class symbol at a varying depth, instance and class symbols together etc…). So symbols are fluid! Each neuron might belong to several symbols. So if symbols overlap, how can we distinguish them? They might differ in the way the neurons are excited. This means that symbols / concept might not exist on the hardware level, but on the software level. If this is true, then intelligence can be realized on non-brain hardware. Our ability to create symbols that are general is what distinguishes us from animals. We often reason about symbols rather than specific objects / events, which is what makes our brains so powerful. Symbols can split and merge, they are far from discrete entities and are incredibly flexible. The way we split and merge them depends upon the collection of our experiences, which is why it’s hard to make an algorithm that replicates it. Symbols are a lossy representation of the objects, so they don’t model them perfectly.

- State: determines how the symbols interact, but it’s also changed by the symbols.

| Unit | Signal | Symbols | State | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ant Colony | Ant | Ant Teams | info for the colony (e.g. there is food that way) | Ant Colony |

| Brain | Neuron | Electrical / Chemical | concepts: a memory, a thought | Brain |

Brains are brains, whether they are made up of ants, neurons, etc… Once you get to a high enough level of abstraction, it’s all the same.

Human thinking is intensional (vs extensional), so descriptions float around, without being anchored to real/specific objects.

Neurons are just analog, ion-based logic gates.

Exact Isomorphism

It’s usually not possible to map precisely one region of the brain to a given brain activity.

Across human brains, the isomorphism is very coarse (only in terms of regions, can’t map specific neurons across brains).

One notable example is the cells of the visual cortex, some of which (hyper complex cells) can even detect complex shapes like a bar moving downwards. So how can we detect complex shapes like faces? There is a lot of processing involved (e.g. seeing a face in 2 different light conditions triggers different sensors, but we still interpret it as the same phenomena). A likely explanation is that each concept has an associated “module” which bundles some neurons together (which don’t have to be exclusive to that module, so each neuron belongs to many symbols). These modules are the symbols of the brain (see the table above).

Approximate Isomorphism

While you can’t exactly map one brain to another in a neuron to neuron way, there is still a concept of similarity between brains.

It would be instructive to be able to pinpoint what this invariant core of human intelligence is, and then to be able to describe the kinds of ‘embellishments’ which can be added to it, making each one of us a unique embodiment of this abstract and mysterious quality called ‘intelligence’.

Brains are similar in the sense that they are the same biological structure and that there are some core symbols that are shared. But also different: e.g. which language we speak, what we have learned over the years etc… which make the neural pathways different (so the start and end point might be the same across brains, but the way they are connected is different).

Is it possible to give a high level description of a brain: yes, but it’s a mess, since our actions depend on both our internal brain structure as well as the external circumstances.

Self / Consciousness

Consciousness: that property of a system that arises whenever there exist symbols in the system which obey triggering patterns like the ones seen above.

Consciousness: modelling the world using symbols (especially the Self symbol, so introspection).

Subsystem: complex type of symbol:is essentially a sub brain, with its own symbols and that can operate independently. used to represent complex symbols (e.g. the self, your best friend, etc..) The subsystems don’t have well-defined borders, and share a lot of info.

The Self: is a symbols It’s special since it keep tracks of the other symbols, meaning it has symbols to represent symbols and things like that. but why does a symbol for the self-exist? to understand everything, the brain relates it to itself, which necessitates the existence of a self object.

AI, Minds and Representing Knowledge

2 Types

- Declarative: explicitly stored

- Procedural: can be generated / inferred from other sources. For humans, it’s essentially the collection of stable, reliable neural pathways.

Why are we so good at problem solving?Because the intuition behind knowing when to backtrack, when to shift levels, to focus on certain details etc… is stored in an intricate web of knowledge that we have built by experiencing life. So it transfers well across domains, and we can perform well even in tasks we have never seen before.

Humans are remarkably good with heuristics (e.g. we play chess well even if we don’t have a lot of computational power because we figured out good heuristic).

Whenever a program outputs something complex (e.g. a mathematical proof) how much credit do we have? It depends on how complex the algorithm is, i.e. how much distance is there between the high level output and it’s atomic components (e.g. single lines of code).

The crux of AI is the representation of knowledge: knowledge in the human brain is not discrete and compartmentalized, but rather chunked, scattered and overlapping with other pieces of knowledge. Mental symbols are all intertwined, it’s hard to create a computational model that describes them accurately.

We label a single object in a variety of ways (e.g. a radio is a thing with knobs, but also a music producer etc…) and different objects can have the same label: each label represents a handle on that object, which is related to how we store it in memory.

Knowledge is not just about storing info, but also how to manipulate it and retrieve according to a lot of different methods: the way it’s stored is almost more important than what is being stored

Humans are also remarkable as we can think of hypotheticals and have different degrees of “almost-happening” (even if they shouldn’t have a scale, as they either happen or not). Language has the semantic capacity to express hypotheticals!

Nested Context Frames: We can express hypotheticals since we model the world through different layers of variability. e.g. constant, parameter and variable are all entities that can vary, but each is tied to a more fundamental layer of our model. The more deeply nested our concepts are, the more we are willing to let them slip and explore adjacent hypotheticals where they are different. (since they are less “fundamental”).

Creativity: it has a mechanical substrate, even if hidden. Randomness is an intrinsic feature of thought (we get it by interacting with a partially random world).